Doctor Faust and the Usurer part 1

Anonymous: Late 16th Century

The author of the socalled Chapbook of Dr. Faust was in all probability a Lutheran pastor. The first known edition appeared...

Eulenspiegel and the Merchant part 3

So they stopped and called Howleglass in a great passion, inquiring what vile work he had been doing, and swore and threatened dreadfully. Just...

Eulenspiegel and the Merchant part 2

Away they went, and the merchant bought some pieces of roasting meat, saying on his return, “Now, Do l, remember when you put this...

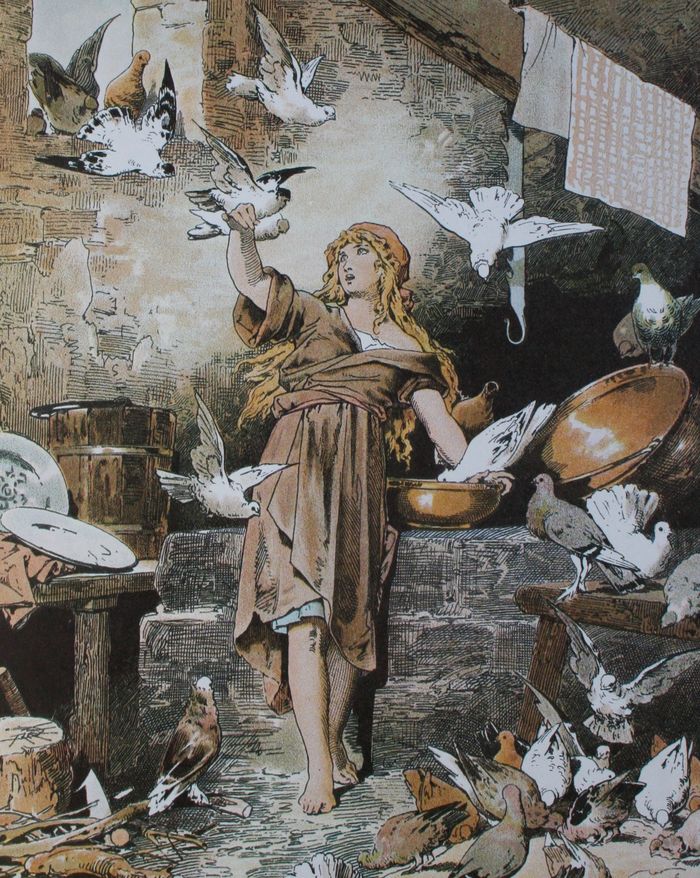

Eulenspiegel and the Merchant part 1

Eulenspiegel and the Merchant (Anonymous: about 1500)

The earliest known version of Eulenspiegel dates from 1515, though an edition is said to have been printed...

Gregorian calendar

The Julian and Gregorian calendars are the accepted conventions of measuring JL Linear Time today. The genesis-area I characteristics of any civilization, however,

I include...

The first museum of Turkey

The first museum of Turkey: St.lrene

The ottoman band of musicians had been organizing concerts in 1914 in st. Irene, the first museum of the...

Indent City of Antiocheia in Pisidia

Yalvac Indent City of Antiocheia in Pisidia

Seeking the distinctive historical texture that underlies the county of Yalvac, we are led to the remains of...

Importance of Anatolia

Importance of Anatolia and Yalvac in the Development of Religions

Anatolia`s generous heart and warm embrace were the tolerant setting for historical events related to...

Money and Interest

Government Bonds Less Interest

When it comes to government bonds, on the other hand, the returns are less interesting. Mathias Bauer, head of Raiffeisen Capital...